Who Can Speak?

Σελίδα 1 από 1

Who Can Speak?

Who Can Speak?

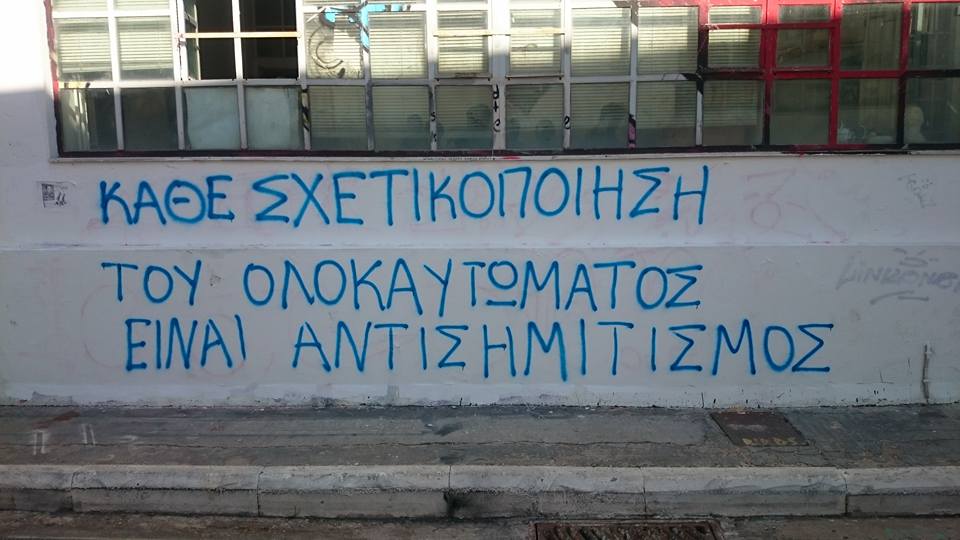

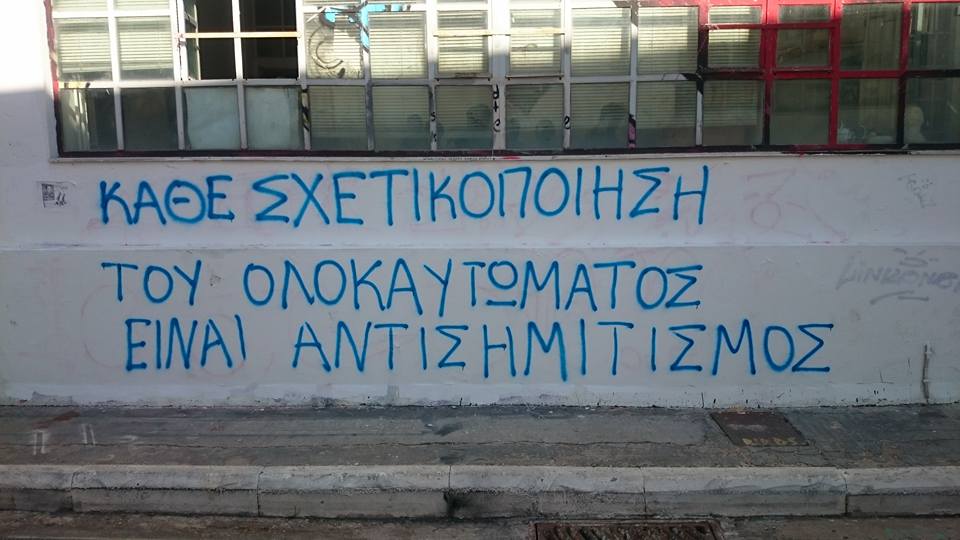

Στην προηγούμενη εκπομπή συνεχίσαμε την συζήτησή μας, παρακολουθώντας τον Ιστορικό της Τέχνης κο Δασκαλοθανάση να τοποθετεί έννοιες, προβληματισμούς και κριτήρια για την «Αντίσταση» που μπορεί να ενέχει ένα έργο τέχνης και άλλα θέματα που σχετίζονται με μια μαύρη κουρτίνα που σκέπασε κάποτε ένα αντίγραφο της Γκερνίκας προς χάριν της αναγγελίας ενός πολέμου. Προχθές ένα θεατρικό έργο κατέβηκε μιας και έκανε χρήση ενός κειμένου του φυλακισμένου Ξηρού. Η υπόθεση του θεατρικού έργου Ισορροπία του Nash στην Πειραματική σκηνή του Εθνικού Θεάτρου, βασιζόταν και σε κείμενο του –φυλακισμένου για τρομοκρατικές ενέργειες– Σάββα Ξηρού. Χθες προκλήθηκε μια αντίδραση για το αναρτημένο έργο - σύνθημα στην είσοδο του κεντρικού κτηρίου της ΑΣΚΤ, που κάναμε και σχετική αναφορά στην προηγούμενη εκπομπή:

Και από πάνω καλύφθηκε με ένα πανό που έγραφε

Κάθε σχετικοποίηση του Ολοκαυτώματος είναι Αντισημιτισμός

https://synelefshenantiastonantishmitismo.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/keimeno.pdf

Μιας και το σχήμα της πινακίδας παραπέμπει στην πινακίδα που ήταν αναρτημένη στην είσοδο του Άουσβιτς αλλά και σε όλα τα άλλα στρατόπεδα συγκέντρωσης. Έγραφε «arbeit macht frei» που σημαίνει «η εργασία σε απελευθερώνει» ή η εργασία σε κάνει ελεύθερο. Φαινόταν εκ πρώτης όψεως ότι το «καλωσόρισμα» των ναζί στο Άουσβιτς ήταν ανθρώπινο με κοινωνική διάσταση, το πραγματικό του νόημα;

Μια δύσκολη συζήτηση θα ανοίξουμε σ΄αυτήν την εκπομπή και η συμβολή άλλων συνομιλητών στην συζήτηση θα ήταν πολύτιμη για μας.

ελπίζουμε να έρθουν άνθρωποι να φωτίσουν τα ερωτήματα που γενούν όλες αυτές οι πράξεις...

Και από πάνω καλύφθηκε με ένα πανό που έγραφε

Κάθε σχετικοποίηση του Ολοκαυτώματος είναι Αντισημιτισμός

https://synelefshenantiastonantishmitismo.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/keimeno.pdf

Μιας και το σχήμα της πινακίδας παραπέμπει στην πινακίδα που ήταν αναρτημένη στην είσοδο του Άουσβιτς αλλά και σε όλα τα άλλα στρατόπεδα συγκέντρωσης. Έγραφε «arbeit macht frei» που σημαίνει «η εργασία σε απελευθερώνει» ή η εργασία σε κάνει ελεύθερο. Φαινόταν εκ πρώτης όψεως ότι το «καλωσόρισμα» των ναζί στο Άουσβιτς ήταν ανθρώπινο με κοινωνική διάσταση, το πραγματικό του νόημα;

Μια δύσκολη συζήτηση θα ανοίξουμε σ΄αυτήν την εκπομπή και η συμβολή άλλων συνομιλητών στην συζήτηση θα ήταν πολύτιμη για μας.

ελπίζουμε να έρθουν άνθρωποι να φωτίσουν τα ερωτήματα που γενούν όλες αυτές οι πράξεις...

The Problem of Speaking For Others

The Problem of Speaking For Others

This was published in Cultural Critique (Winter 1991-92), pp. 5-32; revised and reprinted in Who Can Speak? Authority and Critical Identity edited by Judith Roof and Robyn Wiegman, University of Illinois Press, 1996; and in Feminist Nightmares: Women at Odds edited by Susan Weisser and Jennifer Fleischner, (New York: New York University Press, 1994); and also in Racism and Sexism: Differences and Connections eds. David Blumenfeld and Linda Bell, Rowman and Littlefield, 1995.

Consider the following true stories:

1. Anne Cameron, a very gifted white Canadian author, writes several first person accounts of the lives of Native Canadian women. At the 1988 International Feminist Book Fair in Montreal, a group of Native Canadian writers ask Cameron to, in their words, "move over" on the grounds that her writings are disempowering for Native authors. She agrees.2

2. After the 1989 elections in Panama are overturned by Manuel Noriega, U.S. President George Bush declares in a public address that Noriega's actions constitute an "outrageous fraud" and that "the voice of the Panamanian people have spoken." "The Panamanian people," he tells us, "want democracy and not tyranny, and want Noriega out." He proceeds to plan the invasion of Panama.

3. At a recent symposium at my university, a prestigious theorist was invited to give a lecture on the political problems of post-modernism. Those of us in the audience, including many white women and people of oppressed nationalities and races, wait in eager anticipation for what he has to contribute to this important discussion. To our disappointment, he introduces his lecture by explaining that he can not cover the assigned topic, because as a white male he does not feel that he can speak for the feminist and post-colonial perspectives which have launched the critical interrogation of postmodernism's politics. He lectures instead on architecture.

These examples demonstrate the range of current practices of speaking for others in our society. While the prerogative of speaking for others remains unquestioned in the citadels of colonial administration, among activists and in the academy it elicits a growing unease and, in

some communities of discourse, it is being rejected. There is a strong, albeit contested, current within feminism which holds that speaking for others---even for other women---is arrogant, vain, unethical, and politically illegitimate. Feminist scholarship has a liberatory agenda which almost requires that women scholars speak on behalf of other women, and yet the dangers of speaking across differences of race, culture, sexuality, and power are becoming increasingly clear to all. In feminist magazines such as Sojourner, it is common to find articles and letters in which the author states that she can only speak for herself. In her important paper, "Dyke Methods," Joyce Trebilcot offers a philosophical articulation of this view. She renounces for herself the practice of speaking for others within a lesbian feminist community, arguing that she "will not try to get other wimmin to accept my beliefs in place of their own" on the grounds that to do so would be to practice a kind of discursive coercion and even a violence.3

Feminist discourse is not the only site in which the problem of speaking for others has been acknowledged and addressed. In anthropology there is similar discussion about whether it is possible to speak for others either adequately or justifiably. Trinh T. Minh-ha explains the grounds for skepticism when she says that anthropology is "mainly a conversation of `us' with `us' about `them,' of the white man with the white man about the primitive-nature man...in which `them' is silenced. `Them' always stands on the other side of the hill, naked and speechless...`them' is only admitted among `us', the discussing subjects, when accompanied or introduced by an `us'..."4 Given this analysis, even ethnographies written by progressive anthropologists are a priori regressive because of the structural features of anthropological discursive practice.

The recognition that there is a problem in speaking for others has followed from the widespread acceptance of two claims. First, there has been a growing awareness that where one speaks from affects both the meaning and truth of what one says, and thus that one cannot assume an ability to transcend her location. In other words, a speaker's location (which I take here to refer to her social location or social identity) has an epistemically significant impact on that speaker's claims, and can serve either to authorize or dis-authorize one's speech. The creation of Women's Studies and African American Studies departments were founded on this very belief: that both the study of and the advocacy for the oppressed must come to be done principally by the oppressed themselves, and that we must finally acknowledge that systematic divergences in social location between speakers and those spoken for will have a significant effect on the content of what is said. The unspoken premise here is simply that a speaker's location is epistemically salient. I shall explore this issue further in the next section.

The second claim holds that not only is location epistemically salient, but certain privileged locations are discursively dangerous.5 In particular, the practice of privileged persons speaking for or on behalf of less privileged persons has actually resulted (in many cases) in increasing or reenforcing the oppression of the group spoken for. This was part of the argument made against Anne Cameron's speaking for Native women: Cameron's intentions were never in question, but the effects of her writing were argued to be harmful to the needs of Native authors because it is Cameron rather than they who will be listened to and whose books will be bought by readers interested in Native women. Persons from dominant groups who speak for others are often treated as authenticating presences that confer legitimacy and credibility on the demands of subjugated speakers; such speaking for others does nothing to disrupt the discursive hierarchies that operate in public spaces. For this reason, the work of privileged authors who speak on behalf of the oppressed is becoming increasingly criticized by members of those oppressed groups themselves.6

As social theorists, we are authorized by virtue of our academic positions to develop theories that express and encompass the ideas, needs, and goals of others. However, we must begin to ask ourselves whether this is ever a legitimate authority, and if so, what are the criteria for legitimacy? In particular, is it ever valid to speak for others who are unlike me or who are less privileged than me?

We might try to delimit this problem as only arising when a more privileged person speaks for a less privileged one. In this case, we might say that I should only speak for groups of which I am a member. But this does not tell us how groups themselves should be delimited. For example, can a white woman speak for all women simply by virtue of being a woman? If not, how narrowly should we draw the categories? The complexity and multiplicity of group identifications could result in "communities" composed of single individuals. Moreover, the concept of groups assumes specious notions about clear-cut boundaries and "pure" identities. I am a Panamanian-American and a person of mixed ethnicity and race: half white/Angla and half Panamanian mestiza. The criterion of group identity leaves many unanswered questions for a person such as myself, since I have membership in many conflicting groups but my membership in all of them is problematic. Group identities and boundaries are ambiguous and permeable, and decisions about demarcating identity are always partly arbitrary. Another problem concerns how specific an identity needs to be to confer epistemic authority. Reflection on such problems quickly reveals that no easy solution to the problem of speaking for others can be found by simply restricting the practice to speaking for groups of which one is a member.

Adopting the position that one should only speak for oneself raises similarly difficult questions. If I don't speak for those less privileged than myself, am I abandoning my political responsibility to speak out against oppression, a responsibility incurred by the very fact of my privilege? If I should not speak for others, should I restrict myself to following their lead uncritically? Is my greatest contribution to move over and get out of the way? And if so, what is the best way to do this---to keep silent or to deconstruct my own discourse?

The answers to these questions will certainly depend on who is asking them. While some of us may want to undermine, for example, the U.S. government's practice of speaking for the "Third world," we may not want to undermine someone such as Rigoberta Menchu's ability to speak for Guatemalan Indians.7 So the question arises about whether all instances of speaking for should be condemned and, if not, how we can justify a position which would repudiate some speakers while accepting others.

In order to answer these questions we need to become clearer on the epistemological and metaphysical issues which are involved in the articulation of the problem of speaking for others, issues which most often remain implicit. I will attempt to make these issues clear before turning to discuss some of the possible responses to the problem and advancing a provisional, procedural solution of my own. But first I need to explain further my framing of the problem.

In the examples used above, there may appear to be a conflation between the issue of speaking for others and the issue of speaking about others. This conflation was intentional on my part, because it is difficult to distinguish speaking about from speaking for in all cases. There is an ambiguity in the two phrases: when one is speaking for another one may be describing their situation and thus also speaking about them. In fact, it may be impossible to speak for another without simultaneously conferring information about them. Similarly, when one is speaking about another, or simply trying to describe their situation or some aspect of it, one may also be speaking in place of them, i.e. speaking for them. One may be speaking about another as an advocate or a messenger if the person cannot speak for herself. Thus I would maintain that if the practice of speaking for others is problematic, so too must be the practice of speaking about others.8 This is partly the case because of what has been called the "crisis of representation." For in both the practice of speaking for as well as the practice of speaking about others, I am engaging in the act of representing the other's needs, goals, situation, and in fact, who they are, based on my own situated interpretation. In post-structuralist terms, I am participating in the construction of their subject-positions rather than simply discovering their true selves.

Once we pose it as a problem of representation, we see that, not only are speaking for and speaking about analytically close, so too are the practices of speaking for others and speaking for myself. For, in speaking for myself, I am also representing my self in a certain way, as occupying a specific subject-position, having certain characteristics and not others, and so on. In speaking for myself, I (momentarily) create my self---just as much as when I speak for others I create them as a public, discursive self, a self which is more unified than any subjective experience can support. And this public self will in most cases have an effect on the self experienced as interiority.

The point here is that the problem of representation underlies all cases of speaking for, whether I am speaking for myself or for others. This is not to suggest that all representations are fictions: they have very real material effects, as well as material origins, but they are always mediated in complex ways by discourse, power, and location. However, the problem of speaking for others is more specific than the problem of representation generally, and requires its own particular analysis.

There is one final point I want to make before we can pursue this analysis. The way I have articulated this problem may imply that individuals make conscious choices about their discursive practice free of ideology and the constraints of material reality. This is not what I wish to imply. The problem of speaking for others is a social one, the options available to us are socially constructed, and the practices we engage in cannot be understood as simply the results of autonomous individual choice. Yet to replace both "I" and "we" with a passive voice that erases agency results in an erasure of responsibility and accountability for one's speech, an erasure I would strenuously argue against (there is too little responsibility-taking already in Western practice!). When we sit down to write, or get up to speak, we experience ourselves as making choices. We may experience hesitation from fear of being criticized or from fear of exacerbating a problem we would like to remedy, or we may experience a resolve to speak despite existing obstacles, but in many cases we experience having the possibility to speak or not to speak. On the one hand, a theory which explains this experience as involving autonomous choices free of material structures would be false and ideological, but on the other hand, if we do not acknowledge the activity of choice and the experience of individual doubt, we are denying a reality of our experiential lives.9 So I see the argument of this paper as addressing that small space of discursive agency we all experience, however multi-layered, fictional, and constrained it in fact is.

Ultimately, the question of speaking for others bears crucially on the possibility of political effectivity. Both collective action and coalitions would seem to require the possibility of speaking for. Yet influential postmodernists such as Gilles Deleuze have characterized as "absolutely fundamental: the indignity of speaking for others"10 and important feminist theorists have renounced the practice as irretrievably harmful. What is at stake in rejecting or validating speaking for others as a discursive practice? To answer this, we must become clearer on the epistemological and metaphysical claims which are implicit in the articulation of the problem.

I.

A plethora of sources have argued in this century that the neutrality of the theorizer can no longer, can never again, be sustained, even for a moment. Critical theory, discourses of empowerment, psychoanalytic theory, post-structuralism, feminist and anti-colonialist theories have all concurred on this point. Who is speaking to whom turns out to be as important for meaning and truth as what is said; in fact what is said turns out to change according to who is speaking and who is listening. Following Foucault, I will call these "rituals of speaking" to identify discursive practices of speaking or writing which involve not only the text or utterance but their position within a social space which includes the persons involved in, acting upon, and/or affected by the words. Two elements within these rituals will deserve our attention: the positionality or location of the speaker and the discursive context. We can take the latter to refer to the connections and relations of involvement between the utterance/text and other utterances and texts as well as the material practices in the relevant environment, which should not be confused with an environment spatially adjacent to the particular discursive event.

Rituals of speaking are constitutive of meaning, the meaning of the words spoken as well as the meaning of the event. This claim requires us to shift the ontology of meaning from its location in a text or utterance to a larger space, a space which includes the text or utterance but which also includes the discursive context. And an important implication of this claim is that meaning must be understood as plural and shifting, since a single text can engender diverse meanings given diverse contexts. Not only what is emphasized, noticed, and how it is understood will be affected by the location of both speaker and hearer, but the truth-value or epistemic status will also be affected.

For example, in many situations when a woman speaks the presumption is against her; when a man speaks he is usually taken seriously (unless his speech patterns mark him as socially inferior by dominant standards). When writers from oppressed races and nationalities have insisted that all writing is political the claim has been dismissed as foolish or grounded in ressentiment or it is simply ignored; when prestigious European philosophers say that all writing is political it is taken up as a new and original "truth" (Judith Wilson calls this "the intellectual equivalent of the `cover record'.")11 The rituals of speaking which involve the location of speaker and listeners affect whether a claim is taken as true, well-reasoned, a compelling argument, or a significant idea. Thus, how what is said gets heard depends on who says it, and who says it will affect the style and language in which it is stated. The discursive style in which some European post-structuralists have made the claim that all writing is political marks it as important and likely to be true for a certain (powerful) milieu; whereas the style in which African-American writers made the same claim marked their speech as dismissable in the eyes of the same milieu.

This point might be conceded by those who admit to the political mutability of interpretation, but they might continue to maintain that truth is a different matter altogether. And they would be right that acknowledging the effect of location on meaning and even on whether something is taken as true within a particular discursive context does not entail that the "actual" truth of the claim is contingent upon its context. However, this objection presupposes a particular conception of truth, one in which the truth of a statement can be distinguished from its interpretation and its acceptance. Such a concept would require truth to be independent of the speakers' or listeners' embodied and perspectival location. Thus, the question of whether location bears simply on what is taken to be true or what is really true, and whether such a distinction can be upheld, involves the very difficult problem of the meaning of truth. In the history of Western philosophy, there have existed multiple, competing definitions and ontologies of truth: correspondence, idealist, pragmatist, coherentist, and consensual notions. The dominant modernist view has been that truth represents a relationship of correspondence between a proposition and an extra-discursive reality. On this view, truth is about a realm completely independent of human action and expresses things "as they are in themselves," that is, free of human interpretation.

Arguably since Kant, more obviously since Hegel, it has been widely accepted that an understanding of truth which requires it to be free of human interpretation leads inexorably to skepticism, since it makes truth inaccessible by definition. This created an impetus to reconfigure the ontology of truth, from a locus outside human interpretation to one within it. Hegel, for example, understood truth as an "identity in difference" between subjective and objective elements. Thus, in the Hegelian aftermath, so-called subjective elements, or the historically specific conditions in which human knowledge occurs, are no longer rendered irrelevant or even obstacles to truth.

On a coherentist account of truth, which is held by such philosophers as Rorty, Donald Davidson, Quine, and (I would argue) Gadamer and Foucault, truth is defined as an emergent property of converging discursive and non-discursive elements, when there exists a specific form of integration among these elements in a particular event. Such a view has no necessary relationship to idealism, but it allows us to understand how the social location of the speaker can be said to bear on truth. The speaker's location is one of the elements which converge to produce meaning and thus to determine epistemic validity.12

Let me return now to the formulation of the problem of speaking for others. There are two premises implied by the articulation of the problem, and unpacking these should advance our understanding of the issues involved.

Premise (1): The "ritual of speaking" (as defined above) in which an utterance is located always bears on meaning and truth such that there is no possibility of rendering positionality, location, or context irrelevant to content.

The phrase "bears on" here should indicate some variable amount of influence short of determination or fixing.

One important implication of this first premise is that we can no longer determine the validity of a given instance of speaking for others simply by asking whether or not the speaker has done sufficient research to justify her claims. Adequate research will be a necessary but insufficient criterion of evaluation.

Now let us look at the second premise.

Premise (2): All contexts and locations are differentially related in complex ways to structures of oppression. Given that truth is connected to politics, these political differences between locations will produce epistemic differences as well.

The claim here that "truth is connected to politics" follows necessarily from Premise (1). Rituals of speaking are politically constituted by power relations of domination, exploitation, and subordination. Who is speaking, who is spoken of, and who listens is a result, as well as an act, of political struggle. Simply put, the discursive context is a political arena. To the extent that this context bears on meaning, and meaning is in some sense the object of truth, we cannot make an epistemic evaluation of the claim without simultaneously assessing the politics of the situation.

Although we cannot maintain a neutral voice, according to the first premise we may at least all claim the right and legitimacy to speak. But the second premise suggests that some voices may be dis-authorized on grounds which are simultaneously political and epistemic. Any statement will invoke the structures of power allied with the social location of the speaker, aside from the speaker's intentions or attempts to avoid such invocations.

The conjunction of Premises (1) and (2) suggest that the speaker loses some portion of control over the meaning and truth of her utterance. Given that the context of hearers is partially determinant, the speaker is not the master or mistress of the situation. Speakers may seek to regain control here by taking into account the context of their speech, but they can never know everything about this context, and with written and electronic communication it is becoming increasingly difficult to know anything at all about the context of reception.

This loss of control may be taken by some speakers to mean that no speaker can be held accountable for her discursive actions. The meaning of any discursive event will be shifting and plural, fragmented and even inconsistent. As it ranges over diverse spaces and transforms in the mind of its recipients according to their different horizons of interpretation, the effective control of the speaker over the meanings which she puts in motion may seem negligible. However, a partial loss of control does not entail a complete loss of accountability. And moreover, the better we understand the trajectories by which meanings proliferate, the more likely we can increase, though always only partially, our ability to direct the interpretations and transformations our speech undergoes. When I acknowledge that the listener's social location will affect the meaning of my words, I can more effectively generate the meaning I intend. Paradoxically, the view which holds the speaker or author of a speech act as solely responsible for its meanings ensures the speaker's least effective determinacy over the meanings that are produced.

We do not need to posit the existence of fully conscious acts or containable, fixed meanings in order to hold that speakers can alter their discursive practices and be held accountable for at least some of the effects of these practices. It is a false dilemma to pose the choice here as one between no accountability or complete causal power.

In the next section I shall consider some of the principal responses offered to the problem of speaking for others.

II.

First I want to consider the argument that the very formulation of the problem with speaking for others involves a retrograde, metaphysically insupportable essentialism that assumes one can read off the truth and meaning of what one says straight from the discursive context. Let's call this response the "Charge of Reductionism", because it argues that a sort of reductionist theory of justification (or evaluation) is entailed by premises (1) and (2). Such a reductionist theory might, for example, reduce evaluation to a political assessment of the speaker's location where that location is seen as an insurmountable essence that fixes one, as if one's feet are superglued to a spot on the sidewalk.

For instance, after I vehemently defended Barbara Christian's article, "The Race for Theory," a male friend who had a different evaluation of the piece couldn't help raising the possibility of whether a sort of apologetics structured my response, motivated by a desire to valorize African American writing against all odds. His question in effect raised the issue of the reductionist/essentialist theory of justification I just described.

I, too, would reject reductionist theories of justification and essentialist accounts of what it means to have a location. To say that location bears on meaning and truth is not the same as saying that location determines meaning and truth. And location is not a fixed essence absolutely authorizing one's speech in the way that God's favor absolutely authorized the speech of Moses. Location and positionality should not be conceived as one-dimensional or static, but as multiple and with varying degrees of mobility.13 What it means, then, to speak from or within a group and/or a location is immensely complex. To the extent that location is not a fixed essence, and to the extent that there is an uneasy, underdetermined, and contested relationship between location on the one hand and meaning and truth on the other, we cannot reduce evaluation of meaning and truth to a simple identification of the speaker's location. Neither Premise (1) nor Premise (2) entail reductionism or essentialism. They argue for the relevance of location, not its singular power of determination, and they are non-committal on how to construe the metaphysics of location.

While the "Charge of Reductionism" response has been popular among academic theorists, what I call the "Retreat" response has been popular among some sections of the U.S. feminist movement. This response is simply to retreat from all practices of speaking for; it asserts that one can only know one's own narrow individual experience and one's "own truth" and thus that one can never make claims beyond this. This response is motivated in part by the desire to recognize difference and different priorities, without organizing these differences into hierarchies.

Now, sometimes I think this is the proper response to the problem of speaking for others, depending on who is making it. We certainly want to encourage a more receptive listening on the part of the discursively privileged and to discourage presumptuous and oppressive practices of speaking for. And the desire to retreat sometimes results from the desire to engage in political work but without practicing what might be called discursive imperialism. But a retreat from speaking for will not result in an increase in receptive listening in all cases; it may result merely in a retreat into a narcissistic yuppie lifestyle in which a privileged person takes no responsibility for her society whatsoever. She may even feel justified in exploiting her privileged capacity for personal happiness at the expense of others on the grounds that she has no alternative.

The major problem with such a retreat is that it significantly undercuts the possibility of political effectivity. There are numerous examples of the practice of speaking for others which have been politically efficacious in advancing the needs of those spoken for, from Rigoberta Menchu to Edward Said and Steven Biko. Menchu's efforts to speak for the 33 Indian communities facing genocide in Guatemala have helped to raise money for the revolution and bring pressure against the Guatemalan and U.S. governments who have committed the massacres in collusion. The point is not that for some speakers the danger of speaking for others does not arise, but that in some cases certain political effects can be garnered in no other way.

Joyce Trebilcot's version of the retreat response, which I mentioned at the outset of this essay, raises other issues. She agrees that an absolute prohibition of speaking for would undermine political effectiveness, and therefore says that she will avoid speaking for others only within her lesbian feminist community. So it might be argued that the retreat from speaking for others can be maintained without sacrificing political effectivity if it is restricted to particular discursive spaces. Why might one advocate such a partial retreat? Given that interpretations and meanings are discursive constructions made by embodied speakers, Trebilcot worries that attempting to persuade or speak for another will cut off that person's ability or willingness to engage in the constructive act of developing meaning. Since no embodied speaker can produce more than a partial account, and since the process of producing meaning is necessarily collective, everyone's account within a specified community needs to be encouraged.

I agree with a great deal of Trebilcot's argument. I certainly agree that in some instances speaking for others constitutes a violence and should be stopped. But Trebilcot's position, as well as a more general retreat position, presumes an ontological configuration of the discursive context that simply does not obtain. In particular, it assumes that one can retreat into one's discrete location and make claims entirely and singularly within that location that do not range over others, and therefore that one can disentangle oneself from the implicating networks between one's discursive practices and others' locations, situations, and practices. In other words, the claim that I can speak only for myself assumes the autonomous conception of the self in Classical Liberal theory--that I am unconnected to others in my authentic self or that I can achieve an autonomy from others given certain conditions. But there is no neutral place to stand free and clear in which one's words do not prescriptively affect or mediate the experience of others, nor is there a way to demarcate decisively a boundary between one's location and all others. Even a complete retreat from speech is of course not neutral since it allows the continued dominance of current discourses and acts by omission to reenforce their dominance.

As my practices are made possible by events spatially far away from my body so too my own practices make possible or impossible practices of others. The declaration that I "speak only for myself" has the sole effect of allowing me to avoid responsibility and accountability for my effects on others; it cannot literally erase those effects.

Let me offer an illustration of this. The feminist movement in the U.S. has spawned many kinds of support groups for women with various needs: rape victims, incest survivors, battered wives, and so forth, and some of these groups have been structured around the view that each survivor must come to her own "truth" which ranges only over herself and has no bearing on others. Thus, one woman's experience of sexual assault, its effect on her and her interpretation of it, should not be taken as a universal generalization to which others must subsume or conform their experience. This view works only up to a point. To the extent it recognizes irreducible differences in the way people respond to various traumas and is sensitive to the genuinely variable way in which women can heal themselves, it represents real progress beyond the homogeneous, universalizing approach which sets out one road for all to follow. However, it is an illusion to think that, even in the safe space of a support group, a member of the group can, for example, trivialize brother-sister incest as "sex play" without profoundly harming someone else in the group who is trying to maintain her realistic assessment of her brother's sexual activities with her as a harmful assault against his adult rationalization that "well, for me it was just harmless fun." Even if the speaker offers a dozen caveats about her views as restricted to her location, she will still affect the other woman's ability to conceptualize and interpret her experience and her response to it. And this is simply because we cannot neatly separate off our mediating praxis which interprets and constructs our experiences from the praxis of others. We are collectively caught in an intricate, delicate web in which each action I take, discursive or otherwise, pulls on, breaks off, or maintains the tension in many strands of the web in which others find themselves moving also. When I speak for myself, I am constructing a possible self, a way to be in the world, and am offering that, whether I intend to or not, to others, as one possible way to be.

Thus, the attempt to avoid the problematic of speaking for by retreating into an individualist realm is based on an illusion, well supported in the individualist ideology of the West, that a self is not constituted by multiple intersecting discourses but consists in a unified whole capable of autonomy from others. It is an illusion that I can separate from others to such an extent that I can avoid affecting them. This may be the intention of my speech, and even its meaning if we take that to be the formal entailments of the sentences, but it will not be the effect of the speech, and therefore cannot capture the speech in its reality as a discursive practice. When I "speak for myself" I am participating in the creation and reproduction of discourses through which my own and other selves are constituted.

A further problem with the "Retreat" response is that it may be motivated by a desire to find a method or practice immune from criticism. If I speak only for myself it may appear that I am immune from criticism because I am not making any claims that describe others or prescribe actions for them. If I am only speaking for myself I have no responsibility for being true to your experience or needs.

But surely it is both morally and politically objectionable to structure one's actions around the desire to avoid criticism, especially if this outweighs other questions of effectivity. In some cases, the motivation is perhaps not so much to avoid criticism as to avoid errors, and the person believes that the only way to avoid errors is to avoid all speaking for others. However, errors are unavoidable in theoretical inquiry as well as political struggle, and they usually make contributions. The pursuit of an absolute means to avoid making errors comes perhaps not from a desire to advance collective goals but a desire for personal mastery, to establish a privileged discursive position wherein one cannot be undermined or challenged and thus is master of the situation. From such a position one's own location and positionality would not require constant interrogation and critical reflection; one would not have to constantly engage in this emotionally troublesome endeavor and would be immune from the interrogation of others. Such a desire for mastery and immunity must be resisted.

The final response to the problem of speaking for others that I will consider occurs in Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak's rich essay "Can the Subaltern Speak?"14 Spivak rejects a total retreat from speaking for others, and she criticizes the "self-abnegating intellectual" pose that Foucault and Deleuze adopt when they reject speaking for others on the grounds that their position assumes the oppressed can transparently represent their own true interests. According to Spivak, Foucault and Deleuze's self-abnegation serves only to conceal the actual authorizing power of the retreating intellectuals, who in their very retreat help to consolidate a particular conception of experience (as transparent and self-knowing). Thus, to promote "listening to" as opposed to speaking for essentializes the oppressed as non-ideologically constructed subjects. But Spivak is also critical of speaking for which engages in dangerous re-presentations. In the end Spivak prefers a "speaking to," in which the intellectual neither abnegates his or her discursive role nor presumes an authenticity of the oppressed, but still allows for the possibility that the oppressed will produce a "countersentence" that can then suggest a new historical narrative.

Spivak's arguments show that a simple solution can not be found in for the oppressed or less privileged being able to speak for themselves, since their speech will not necessarily be either liberatory or reflective of their "true interests", if such exist. I agree with her on this point but I would emphasize also that ignoring the subaltern's or oppressed person's speech is, as she herself notes, "to continue the imperialist project."15 Even if the oppressed person's speech is not liberatory in its content, it remains the case that the very act of speaking itself constitutes a subject that challenges and subverts the opposition between the knowing agent and the object of knowledge, an opposition which has served as a key player in the reproduction of imperialist modes of discourse. Thus, the problem with speaking for others exists in the very structure of discursive practice, irrespective of its content, and subverting the hierarchical rituals of speaking will always have some liberatory effects.

I agree, then, that we should strive to create wherever possible the conditions for dialogue and the practice of speaking with and to rather than speaking for others. Often the possibility of dialogue is left unexplored or inadequately pursued by more privileged persons. Spaces in which it may seem as if it is impossible to engage in dialogic encounters need to be transformed in order to do so, such as classrooms, hospitals, workplaces, welfare agencies, universities, institutions for international development and aid, and governments. It has long been noted that existing communication technologies have the potential to produce these kinds of interaction even though research and development teams have not found it advantageous under capitalism to do so.

However, while there is much theoretical and practical work to be done to develop such alternatives, the practice of speaking for others remains the best option in some existing situations. An absolute retreat weakens political effectivity, is based on a metaphysical illusion, and often effects only an obscuring of the intellectual's power. There can be no complete or definitive solution to the problem of speaking for others, but there is a possibility that its dangers can be decreased. The remainder of this paper will try to contribute toward developing that possibility.

III.

In rejecting a general retreat from speaking for, I am not advocating a return to an unself-conscious appropriation of the other, but rather that anyone who speaks for others should only do so out of a concrete analysis of the particular power relations and discursive effects involved. I want to develop this point by elucidating four sets of interrogatory practices which are meant to help evaluate possible and actual instances of speaking for. In list form they may appear to resemble an algorithm, as if we could plug in an instance of speaking for and factor out an analysis and evaluation. However, they are meant only to suggest the questions that should be asked concerning any such discursive practice. These are by no means original: they have been learned and practiced by many activists and theorists.

(1) The impetus to speak must be carefully analyzed and, in many cases (certainly for academics!), fought against. This may seem an odd way to begin discussing how to speak for, but the point is that the impetus to always be the speaker and to speak in all situations must be seen for what it is: a desire for mastery and domination. If one's immediate impulse is to teach rather than listen to a less-privileged speaker, one should resist that impulse long enough to interrogate it carefully. Some of us have been taught that by right of having the dominant gender, class, race, letters after our name, or some other criterion, we are more likely to have the truth. Others have been taught the opposite and will speak haltingly, with apologies, if they speak at all.16

At the same time, we have to acknowledge that the very decision to "move over" or retreat can occur only from a position of privilege. Those who are not in a position of speaking at all cannot retreat from an action they do not employ. Moreover, making the decision for oneself whether or not to retreat is an extension or application of privilege, not an abdication of it. Still, it is sometimes called for.

(2) We must also interrogate the bearing of our location and context on what it is we are saying, and this should be an explicit part of every serious discursive practice we engage in. Constructing hypotheses about the possible connections between our location and our words is one way to begin. This procedure would be most successful if engaged in collectively with others, by which aspects of our location less obvious to us might be revealed.17

One deformed way in which this is too often carried out is when speakers offer up in the spirit of "honesty" autobiographical information about themselves, usually at the beginning of their discourse as a kind of disclaimer. This is meant to acknowledge their own understanding that they are speaking from a specified, embodied location without pretense to a transcendental truth. But as Maria Lugones and others have forcefully argued, such an act serves no good end when it is used as a disclaimer against one's ignorance or errors and is made without critical interrogation of the bearing of such an autobiography on what is about to be said. It leaves for the listeners all the real work that needs to be done. For example, if a middle class white man were to begin a speech by sharing with us this autobiographical information and then using it as a kind of apologetics for any limitations of his speech, this would leave to those of us in the audience who do not share his social location all the work of translating his terms into our own, apprising the applicability of his analysis to our diverse situation, and determining the substantive relevance of his location on his claims. This is simply what less-privileged persons have always had to do for ourselves when reading the history of philosophy, literature, etc., which makes the task of appropriating these discourses more difficult and time-consuming (and alienation more likely to result). Simple unanalyzed disclaimers do not improve on this familiar situation and may even make it worse to the extent that by offering such information the speaker may feel even more authorized to speak and be accorded more authority by his peers.

(3) Speaking should always carry with it an accountability and responsibility for what one says. To whom one is accountable is a political/epistemological choice contestable, contingent and, as Donna Haraway says, constructed through the process of discursive action. What this entails in practice is a serious commitment to remain open to criticism and to attempt actively, attentively, and sensitively to "hear" the criticism (understand it). A quick impulse to reject criticism must make one wary.

(4) Here is my central point. In order to evaluate attempts to speak for others in particular instances, we need to analyze the probable or actual effects of the words on the discursive and material context. One cannot simply look at the location of the speaker or her credentials to speak; nor can one look merely at the propositional content of the speech; one must also look at where the speech goes and what it does there.

Looking merely at the content of a set of claims without looking at their effects cannot produce an adequate or even meaningful evaluation of it, and this is partly because the notion of a content separate from effects does not hold up. The content of the claim, or its meaning, emerges in interaction between words and hearers within a very specific historical situation. Given this, we have to pay careful attention to the discursive arrangement in order to understand the full meaning of any given discursive event. For example, in a situation where a well-meaning First world person is speaking for a person or group in the Third world, the very discursive arrangement may reinscribe the "hierarchy of civilizations" view where the U. S. lands squarely at the top. This effect occurs because the speaker is positioned as authoritative and empowered, as the knowledgeable subject, while the group in the Third World is reduced, merely because of the structure of the speaking practice, to an object and victim that must be championed from afar. Though the speaker may be trying to materially improve the situation of some lesser-privileged group, one of the effects of her discourse is to reenforce racist, imperialist conceptions and perhaps also to further silence the lesser-privileged group's own ability to speak and be heard.18 This shows us why it is so important to reconceptualize discourse, as Foucault recommends, as an event, which includes speaker, words, hearers, location, language, and so on.

All such evaluations produced in this way will be of necessity indexed. That is, they will obtain for a very specific location and cannot be taken as universal. This simply follows from the fact that the evaluations will be based on the specific elements of historical discursive context, location of speakers and hearers, and so forth. When any of these elements is changed, a new evaluation is called for.

Our ability to assess the effects of a given discursive event is limited; our ability to predict these effects is even more difficult. When meaning is plural and deferred, we can never hope to know the totality of effects. Still, we can know some of the effects our speech generates: I can find out, for example, that the people I spoke for are angry that I did so or appreciative. By learning as much as possible about the context of reception I can increase my ability to discern at least some of the possible effects. This mandates incorporating a more dialogic approach to speaking, that would include learning from and about the domains of discourse my words will affect.

I want to illustrate the implications of this fourth point by applying it to the examples I gave at the beginning. In the case of Anne Cameron, if the effects of her books are truly disempowering for Native women, they are counterproductive to Cameron's own stated intentions, and she should indeed "move over." In the case of the white male theorist who discussed architecture instead of the politics of postmodernism, the effect of his refusal was that he offered no contribution to an important issue and all of us there lost an opportunity to discuss and explore it.

Now let me turn to the example of George Bush. When Bush claimed that Noriega is a corrupt dictator who stands in the way of democracy in Panama, he repeated a claim which has been made almost word for word by the Opposition movement in Panama. Yet the effects of the two statements are vastly different because the meaning of the claim changes radically depending on who states it. When the president of the United States stands before the world passing judgement on a Third World government, and criticizing it on the basis of corruption and a lack of democracy, the immediate effect of this statement, as opposed to the Opposition's, is to reenforce the prominent Anglo view that Latin American corruption is the primary cause of the region's poverty and lack of democracy, that the U.S. is on the side of democracy in the region, and that the U.S. opposes corruption and tyranny. Thus, the effect of a U.S. president's speaking for Latin America in this way is to re-consolidate U.S. imperialism by obscuring its true role in the region in torturing and murdering hundreds and thousands of people who have tried to bring democratic and progressive governments into existence. And this effect will continue until the U.S. government admits its history of international mass murder and radically alters it foreign policy.

IV. Conclusion

This issue is complicated by the variable way in which the importance of the source, or location of the author, can be understood, a topic alluded to earlier. On one view, the author of a text is its "owner" and "originator" credited with creating its ideas and with being their authoritative interpreter. On another view, the original speaker or writer is no more privileged than any other person who articulates these views, and in fact the "author" cannot be identified in a strict sense because the concept of author is an ideological construction many abstractions removed from the way in which ideas emerge and become material forces.19 Now, does this latter position mean that the source or locatedness of the author is irrelevant?

It need not entail this conclusion, though it might in some formulations. We can de-privilege the "original" author and reconceptualize ideas as traversing (almost) freely in a discursive space, available from many locations, and without a clearly identifiable originary track, and yet retain our sense that source remains relevant to effect. Our meta-theory of authorship does not preclude the material reality that in discursive spaces there is a speaker or writer credited as the author of her utterances, or that for example the feminist appropriation of the concept "patriarchy" gets tied to Kate Millett, a white Anglo feminist, or that the term feminism itself has been and is associated with a Western origin. These associations have an effect, an effect of producing distrust on the part of some Third World nationalists, an effect of reinscribing semi-conscious imperialist attitudes on the part of some first world feminists. These are not the only possible effects, and some of the effects may not be pernicious, but all the effects must be taken into account when evaluating the discourse of "patriarchy."

The emphasis on effects should not imply, therefore, that an examination of the speaker's location is any less crucial. This latter examination might be called a kind of genealogy. In this sense, a genealogy involves asking how a position or view is mediated and constituted through and within the conjunction and conflict of historical, cultural, economic, psychological, and sexual practices. But it seems to me that the importance of the source of a view, and the importance of doing a genealogy, should be subsumed within an overall analysis of effects, making the central question what the effects are of the view on material and discursive practices through which it traverses and the particular configuration of power relations emergent from these. Source is relevant only to the extent that it has an impact on effect. As Gayatri Spivak likes to say, the invention of the telephone by a European upper class male in no way preempts its being put to the use of an anti-imperialist revolution.

In conclusion, I would stress that the practice of speaking for others is often born of a desire for mastery, to privilege oneself as the one who more correctly understands the truth about another's situation or as one who can champion a just cause and thus achieve glory and praise. And the effect of the practice of speaking for others is often, though not always, erasure and a reinscription of sexual, national, and other kinds of hierarchies. I hope that this analysis will contribute toward rather than diminish the important discussion going on today about how to develop strategies for a more equitable, just distribution of the ability to speak and be heard. But this development should not be taken as an absolute dis-authorization of all practices of speaking for. It is not always the case that when others unlike me speak for me I have ended up worse off, or that when we speak for others they end up worse off. Sometimes, as Loyce Stewart has argued, we do need a "messenger" to advocate for our needs.

The source of a claim or discursive practice in suspect motives or maneuvers or in privileged social locations, I have argued, though it is always relevant, cannot be sufficient to repudiate it. We must ask further questions about its effects, questions which amount to the following: will it enable the empowerment of oppressed peoples?

Linda Martín Alcoff

Department of Philosophy

Syracuse University

Syracuse New York 13244

Endnotes:

1 I am grateful to the following for their generous help with this paper: Eastern Society for Women in Philosophy, the Central New York Women Philosopher's Group, Loyce Stewart, Richard Schmitt, Sandra Bartky, Laurence Thomas, Leslie Bender, Robyn Wiegman, Anita Canizares Molina, and Felicity Nussbaum.

2 See Lee Maracle, "Moving Over," in Trivia 14 (Spring 89): 9-10.

3 Joyce Trebilcot, "Dyke Methods," Hypatia 3.2 (Summer 1988): 1. Trebilcot is explaining here her own reasoning for rejecting these practices, but she is not advocating that other women join her in this. Thus, her argument does not fall into a self-referential incoherence.

4 Trinh T. Minh-ha, Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989), 65 and 67. For examples of anthropologist's concern with this issue see Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography ed. James Clifford and George E. Marcus (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986); James Clifford "On Ethnographic Authority" Representations 1.2: 118-146; Anthropology as Cultural Critique ed. George Marcus and Michael Fischer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986); Paul Rabinow "Discourse and Power: On the Limits of Ethnographic Texts" Dialectical Anthropology, 10.1 and 2 (July 85): 1-14.

5 To be privileged here will mean to be in a more favorable, mobile, and dominant position vis-a-vis the structures of power/knowledge in a society. Thus privilege carries with it, e.g., presumption in one's favor when one speaks. Certain races, nationalities, genders, sexualities, and classes confer privilege, but a single individual (perhaps most individuals) may enjoy privilege in respect to some parts of their identity and a lack of privilege in respect to other parts. Therefore, privilege must always be indexed to specific relationships as well as to specific locations.

The term privilege is not meant to include positions of discursive power achieved through merit, but in any case these are rarely pure. In other words, some persons are accorded discursive authority because they are respected leaders or because they are teachers in a classroom and know more about the material at hand. So often, of course, the authority of such persons based on their merit combines with the authority they may enjoy by virtue of their having the dominant gender, race, class, or sexuality. It is the latter sources of authority that I am referring to by the term "privilege."

6 See also Maria Lugones and Elizabeth Spelman, "Have We Got a Theory For You! Cultural Imperialism, Feminist Theory and the Demand for the Women's Voice" Women's Studies International Forum 6.6 (1983): 573-81. In their paper Lugones and Spelman explore the way in which the "demand for the women's voice" disempowered women of color by not attending to the differences in privilege within the category of women, resulting in a privileging of white women's voices only. They explore the effects this has had on the making of theory within feminism, and attempt to find "ways of talking or being talked about that are helpful, illuminating, empowering, respectful." (p. 25) This essay takes inspiration from theirs and is meant to continue their discussion.

7 See her I...Rigoberta Menchu, ed. Elisabeth Burgos-Debray, trans. Ann Wright (London: Verso, 1984). (The use of the term "Indian" here follows Menchu's use.)

8 E.g., if it is the case that no "descriptive" discourse is normative- or value-free, then no discourse is free of some kind of advocacy, and all speaking about will involve speaking for someone, ones, or something.

9 Another distinction that might be made is between different material practices of speaking for: giving a speech, writing an essay or book, making a movie or tv program, as well as hearing, reading, watching and so on. I will not address the possible differences that arise from these different practices, and will address myself to the (fictional) "generic" practice of speaking for.

10 Deleuze in a conversation with Foucault, "Intellectuals and Power" in Language, Counter-Memory, Practice ed. Donald Bouchard, trans. Donald Bouchard and Sherry Simon (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977): 209.

11 See her "Down to the Crossroads: The Art of Alison Saar," Third Text 10 (Spring 90), for a discussion of this phenomenon in the artworld, esp. page 36. See also Barbara Christian "The Race for Theory" Feminist Studies 14.1 (Spring 88): 67-79; and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. "Authority, (White) Power and the (Black) Critic; It's All Greek To Me" Cultural Critique 7 (Fall 87): 19-46.

12 I know that my insistence on using the word "truth" swims upstream of current postmodernist orthodoxies. This insistence is not based on a commitment to transparent accounts of representation or a correspondence theory of truth, but on my belief that the demarcation between epistemically better and worse claims continues to operate (indeed, it is inevitable) and that what happens when we eschew all epistemological issues of truth is that the terms upon which those demarcations are made go unseen and uncontested. A very radical revision of what we mean by truth is in order, but if we ignore the ways in which our discourses appeal to some version of truth for their persuasiveness we are in danger of remaining blind to the operations of legitimation that function within our own texts. The task is therefore to explicate the relations between politics and knowledge rather than pronounce the death of truth. See my Real Knowing, forthcoming with Cornell University Press.

13 Cf. my "Cultural Feminism versus Post-Structuralism: The Identity Crisis in Feminist Theory" SIGNS: A Journal of Women in Culture and Society 13.3 (Spring 1988): 405-36. For more discussions on the multi-dimensionality of social identity see Maria Lugones "Playfulness, `World'-Travelling, and Loving Perception," Hypatia 2.2: 3-19; and Gloria Anzaldua, Borderlands/La Frontera (San Francisco: Spinsters/Aunt Lute Book Company, 1987).

14 This can be found in Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture ed. Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1988): 271-313.

15 Ibid, p. 298.

16 See Edward Said, "Representing the Colonized: Anthropology's Interlocutors" Critical Inquiry 15.2 (Winter 1989), p. 219, on this point, where he shows how the "dialogue" between Western anthropology and colonized people have been non-reciprocal, and supports the need for the Westerners to begin to stop talking.

17 See again Said, "Representing the Colonized" p. 212, where he encourages in particular the self-interrogation of privileged speakers. This seems to be a running theme in what are sometimes called "minority discourses" these days: asserting the need for whites to study whiteness, e.g. The need for an interrogation of one's location exists with every discursive event by any speaker, but given the lopsidedness of current "dialogues" it seems especially important to push for this among the privileged, who sometimes seem to want to study everybody's social and cultural construction but their own.

18 To argue for the relevance of effects for evaluation does not entail that there is only one way to do such an accounting or what kind of effects will be deemed desirable. How one evaluates a particular effect is left open; (4) argues simply that effects must always be taken into account.

19 I like the way Susan Bordo makes this point. In speaking about theories or ideas that gain prominence, she says: "...all cultural formations...[are] complexly constructed out of diverse elements---intellectual, psychological, institutional, and sociological. Arising not from monolithic design but from an interplay of factors and forces, it is best understood not as a discrete, definable position which can be adopted or rejected, but as an emerging coherence which is being fed by a variety of currents, sometimes overlapping, sometimes quite distinct." See her "Feminism, Postmodernism, and Gender-Skepticism" in Feminism/Postmodernism ed. Linda Nicholson (New York, Routledge, 1989), p. 135. If ideas arise in such a configuration of forces, does it make sense to ask for an author?

Consider the following true stories:

1. Anne Cameron, a very gifted white Canadian author, writes several first person accounts of the lives of Native Canadian women. At the 1988 International Feminist Book Fair in Montreal, a group of Native Canadian writers ask Cameron to, in their words, "move over" on the grounds that her writings are disempowering for Native authors. She agrees.2

2. After the 1989 elections in Panama are overturned by Manuel Noriega, U.S. President George Bush declares in a public address that Noriega's actions constitute an "outrageous fraud" and that "the voice of the Panamanian people have spoken." "The Panamanian people," he tells us, "want democracy and not tyranny, and want Noriega out." He proceeds to plan the invasion of Panama.

3. At a recent symposium at my university, a prestigious theorist was invited to give a lecture on the political problems of post-modernism. Those of us in the audience, including many white women and people of oppressed nationalities and races, wait in eager anticipation for what he has to contribute to this important discussion. To our disappointment, he introduces his lecture by explaining that he can not cover the assigned topic, because as a white male he does not feel that he can speak for the feminist and post-colonial perspectives which have launched the critical interrogation of postmodernism's politics. He lectures instead on architecture.

These examples demonstrate the range of current practices of speaking for others in our society. While the prerogative of speaking for others remains unquestioned in the citadels of colonial administration, among activists and in the academy it elicits a growing unease and, in

some communities of discourse, it is being rejected. There is a strong, albeit contested, current within feminism which holds that speaking for others---even for other women---is arrogant, vain, unethical, and politically illegitimate. Feminist scholarship has a liberatory agenda which almost requires that women scholars speak on behalf of other women, and yet the dangers of speaking across differences of race, culture, sexuality, and power are becoming increasingly clear to all. In feminist magazines such as Sojourner, it is common to find articles and letters in which the author states that she can only speak for herself. In her important paper, "Dyke Methods," Joyce Trebilcot offers a philosophical articulation of this view. She renounces for herself the practice of speaking for others within a lesbian feminist community, arguing that she "will not try to get other wimmin to accept my beliefs in place of their own" on the grounds that to do so would be to practice a kind of discursive coercion and even a violence.3

Feminist discourse is not the only site in which the problem of speaking for others has been acknowledged and addressed. In anthropology there is similar discussion about whether it is possible to speak for others either adequately or justifiably. Trinh T. Minh-ha explains the grounds for skepticism when she says that anthropology is "mainly a conversation of `us' with `us' about `them,' of the white man with the white man about the primitive-nature man...in which `them' is silenced. `Them' always stands on the other side of the hill, naked and speechless...`them' is only admitted among `us', the discussing subjects, when accompanied or introduced by an `us'..."4 Given this analysis, even ethnographies written by progressive anthropologists are a priori regressive because of the structural features of anthropological discursive practice.

The recognition that there is a problem in speaking for others has followed from the widespread acceptance of two claims. First, there has been a growing awareness that where one speaks from affects both the meaning and truth of what one says, and thus that one cannot assume an ability to transcend her location. In other words, a speaker's location (which I take here to refer to her social location or social identity) has an epistemically significant impact on that speaker's claims, and can serve either to authorize or dis-authorize one's speech. The creation of Women's Studies and African American Studies departments were founded on this very belief: that both the study of and the advocacy for the oppressed must come to be done principally by the oppressed themselves, and that we must finally acknowledge that systematic divergences in social location between speakers and those spoken for will have a significant effect on the content of what is said. The unspoken premise here is simply that a speaker's location is epistemically salient. I shall explore this issue further in the next section.

The second claim holds that not only is location epistemically salient, but certain privileged locations are discursively dangerous.5 In particular, the practice of privileged persons speaking for or on behalf of less privileged persons has actually resulted (in many cases) in increasing or reenforcing the oppression of the group spoken for. This was part of the argument made against Anne Cameron's speaking for Native women: Cameron's intentions were never in question, but the effects of her writing were argued to be harmful to the needs of Native authors because it is Cameron rather than they who will be listened to and whose books will be bought by readers interested in Native women. Persons from dominant groups who speak for others are often treated as authenticating presences that confer legitimacy and credibility on the demands of subjugated speakers; such speaking for others does nothing to disrupt the discursive hierarchies that operate in public spaces. For this reason, the work of privileged authors who speak on behalf of the oppressed is becoming increasingly criticized by members of those oppressed groups themselves.6

As social theorists, we are authorized by virtue of our academic positions to develop theories that express and encompass the ideas, needs, and goals of others. However, we must begin to ask ourselves whether this is ever a legitimate authority, and if so, what are the criteria for legitimacy? In particular, is it ever valid to speak for others who are unlike me or who are less privileged than me?

We might try to delimit this problem as only arising when a more privileged person speaks for a less privileged one. In this case, we might say that I should only speak for groups of which I am a member. But this does not tell us how groups themselves should be delimited. For example, can a white woman speak for all women simply by virtue of being a woman? If not, how narrowly should we draw the categories? The complexity and multiplicity of group identifications could result in "communities" composed of single individuals. Moreover, the concept of groups assumes specious notions about clear-cut boundaries and "pure" identities. I am a Panamanian-American and a person of mixed ethnicity and race: half white/Angla and half Panamanian mestiza. The criterion of group identity leaves many unanswered questions for a person such as myself, since I have membership in many conflicting groups but my membership in all of them is problematic. Group identities and boundaries are ambiguous and permeable, and decisions about demarcating identity are always partly arbitrary. Another problem concerns how specific an identity needs to be to confer epistemic authority. Reflection on such problems quickly reveals that no easy solution to the problem of speaking for others can be found by simply restricting the practice to speaking for groups of which one is a member.

Adopting the position that one should only speak for oneself raises similarly difficult questions. If I don't speak for those less privileged than myself, am I abandoning my political responsibility to speak out against oppression, a responsibility incurred by the very fact of my privilege? If I should not speak for others, should I restrict myself to following their lead uncritically? Is my greatest contribution to move over and get out of the way? And if so, what is the best way to do this---to keep silent or to deconstruct my own discourse?

The answers to these questions will certainly depend on who is asking them. While some of us may want to undermine, for example, the U.S. government's practice of speaking for the "Third world," we may not want to undermine someone such as Rigoberta Menchu's ability to speak for Guatemalan Indians.7 So the question arises about whether all instances of speaking for should be condemned and, if not, how we can justify a position which would repudiate some speakers while accepting others.

In order to answer these questions we need to become clearer on the epistemological and metaphysical issues which are involved in the articulation of the problem of speaking for others, issues which most often remain implicit. I will attempt to make these issues clear before turning to discuss some of the possible responses to the problem and advancing a provisional, procedural solution of my own. But first I need to explain further my framing of the problem.

In the examples used above, there may appear to be a conflation between the issue of speaking for others and the issue of speaking about others. This conflation was intentional on my part, because it is difficult to distinguish speaking about from speaking for in all cases. There is an ambiguity in the two phrases: when one is speaking for another one may be describing their situation and thus also speaking about them. In fact, it may be impossible to speak for another without simultaneously conferring information about them. Similarly, when one is speaking about another, or simply trying to describe their situation or some aspect of it, one may also be speaking in place of them, i.e. speaking for them. One may be speaking about another as an advocate or a messenger if the person cannot speak for herself. Thus I would maintain that if the practice of speaking for others is problematic, so too must be the practice of speaking about others.8 This is partly the case because of what has been called the "crisis of representation." For in both the practice of speaking for as well as the practice of speaking about others, I am engaging in the act of representing the other's needs, goals, situation, and in fact, who they are, based on my own situated interpretation. In post-structuralist terms, I am participating in the construction of their subject-positions rather than simply discovering their true selves.

Once we pose it as a problem of representation, we see that, not only are speaking for and speaking about analytically close, so too are the practices of speaking for others and speaking for myself. For, in speaking for myself, I am also representing my self in a certain way, as occupying a specific subject-position, having certain characteristics and not others, and so on. In speaking for myself, I (momentarily) create my self---just as much as when I speak for others I create them as a public, discursive self, a self which is more unified than any subjective experience can support. And this public self will in most cases have an effect on the self experienced as interiority.

The point here is that the problem of representation underlies all cases of speaking for, whether I am speaking for myself or for others. This is not to suggest that all representations are fictions: they have very real material effects, as well as material origins, but they are always mediated in complex ways by discourse, power, and location. However, the problem of speaking for others is more specific than the problem of representation generally, and requires its own particular analysis.

There is one final point I want to make before we can pursue this analysis. The way I have articulated this problem may imply that individuals make conscious choices about their discursive practice free of ideology and the constraints of material reality. This is not what I wish to imply. The problem of speaking for others is a social one, the options available to us are socially constructed, and the practices we engage in cannot be understood as simply the results of autonomous individual choice. Yet to replace both "I" and "we" with a passive voice that erases agency results in an erasure of responsibility and accountability for one's speech, an erasure I would strenuously argue against (there is too little responsibility-taking already in Western practice!). When we sit down to write, or get up to speak, we experience ourselves as making choices. We may experience hesitation from fear of being criticized or from fear of exacerbating a problem we would like to remedy, or we may experience a resolve to speak despite existing obstacles, but in many cases we experience having the possibility to speak or not to speak. On the one hand, a theory which explains this experience as involving autonomous choices free of material structures would be false and ideological, but on the other hand, if we do not acknowledge the activity of choice and the experience of individual doubt, we are denying a reality of our experiential lives.9 So I see the argument of this paper as addressing that small space of discursive agency we all experience, however multi-layered, fictional, and constrained it in fact is.

Ultimately, the question of speaking for others bears crucially on the possibility of political effectivity. Both collective action and coalitions would seem to require the possibility of speaking for. Yet influential postmodernists such as Gilles Deleuze have characterized as "absolutely fundamental: the indignity of speaking for others"10 and important feminist theorists have renounced the practice as irretrievably harmful. What is at stake in rejecting or validating speaking for others as a discursive practice? To answer this, we must become clearer on the epistemological and metaphysical claims which are implicit in the articulation of the problem.

I.